Citizen science in Kenya’s water towers

A simple, inexpensive way to monitor water across landscapes

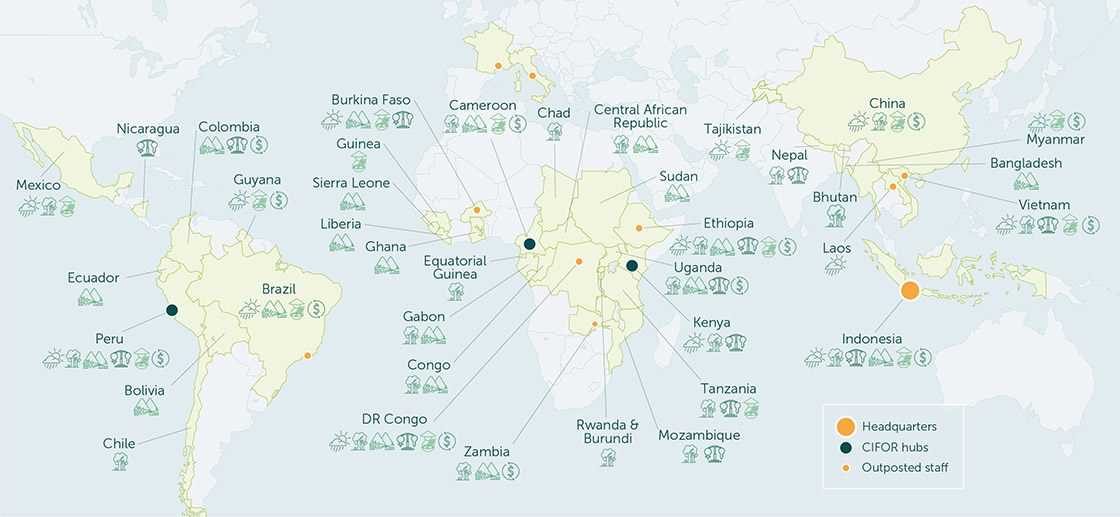

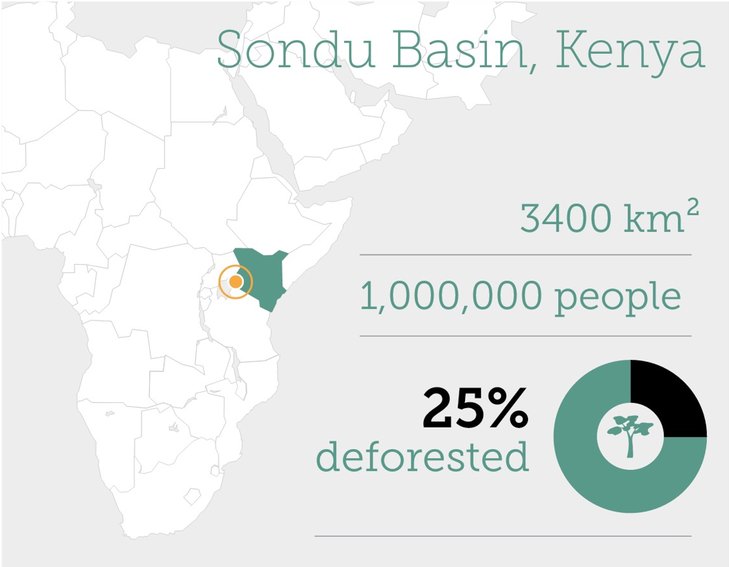

Millions of rural and urban people rely on Kenya’s mountain forests for food, livestock fodder, woodfuel – and fresh water. But these forests – called ‘water towers’ – are being cleared for agriculture, charcoal and new settlements, affecting water supplies downstream. And seasonal rains are less predictable, making it a challenge for authorities to set yearly water plans and to deal with flash floods and drought.

Exactly how each type of land use affects the water isn’t known. To fill the data gap, CIFOR started monitoring water levels and quality in the Sondu Basin of South-West Mau in 2014 using automatic sensors. These generated the first ever precise data set of water flow and water quality information, available continuously over two years. But these automated stations are costly to install and maintain.

A new phase of the project is enlisting the help of those with the most intimate knowledge of local resources: the men and women who use the rivers and forests for daily living.

Locals have been trained to read water-level gauges installed along the river and send in their measurements by SMS. Most villagers have mobile phones, and while not everyone sees the benefit of participating, many are enthusiastic.

Water is key to life and should always be protected by all means. The daily readings and reporting will help plan for its security.

Teresa Adhiambo, Chair of the Sondu Water Resource Users Association

How more people can be enlisted to participate in the data collection, and how these ‘crowd-sourced’ data compare to the scientific data from the automated station is currently subject of a PhD study by a young Kenyan researcher. If the usefulness of the citizen data is confirmed, not only will a simple, low-cost way to inform sustainable water management planning have been found, it will also encourage communities to take an active role in managing their water resources.

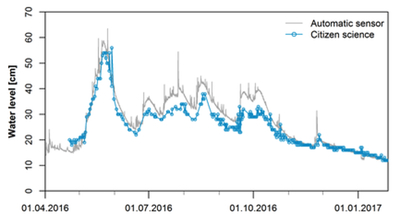

Data check

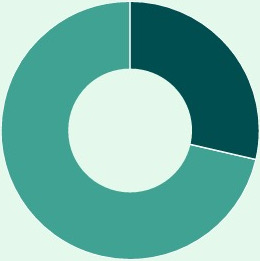

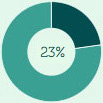

So far, water-level readings sent in by local users match up with the high-resolution data from the automatic monitoring stations and with discharge measurements by the Water Resource Management Authority, showing that citizen science works.

So far, water-level readings sent in by local users match up with the high-resolution data from the automatic monitoring stations and with discharge measurements by the Water Resource Management Authority, showing that citizen science works.

Early gender lessons

Women visit the river daily to fetch water and wash clothes, making them ideal water monitors. But men are the ones sending the most data. As the project evolves, researchers are looking for ways to motivate all water users – women and men alike – to become citizen scientists.

Next steps

Long-term data are needed before any conclusions can be drawn about how different land uses affect water in the Sondu Basin. Researchers are training local volunteers and members of Water Resource Users Associations to assess water quality and will compare results with the automatic sensor readings. They’re also exploring incentive mechanisms to get more people involved.

When we see the changes in water level we are able to know if the forests are being cleared.

Samson, citizen scientist, Kuresoi station

Photo by S. Jacobs/CIFOR.

Related posts

New CIFOR project – Engaging citizen scientists to secure fresh water in Kenya

Ensuring everyone has enough water is especially important in countries with high poverty rates and which are undergoing rapid economic development. Land use change can put stress on water availability and quality, as it has done in Kenya with the large-scale loss of forests.

Researchers study future of Kenya’s ‘last big mountain forest’

When the Mau Forest suffers, so do an estimated 6 million Kenyans who depend on it for their water.